Every time you see your social worker, you worry you will be taken away again. He or she asks you questions about abuse or physical and emotional neglect, but language fails you. They introduce you to people who will be your new parents, probably temporarily.

You don’t want to be here — wherever it is that you are —and you can’t imagine what could be next.

This is what the traumatic experience of being a foster kid is like. I can vouch for it because I was a child in the foster care system, and I have suffered its lasting effects.

The AFCARS Report also states that each year, nearly 18,000 children will never reunite with family or join a new one at all.

As I did, they will emancipate or age out of the system — alone.

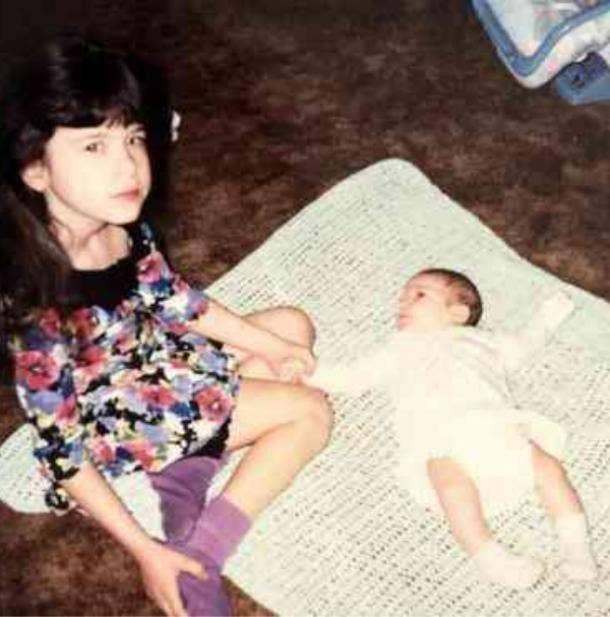

My journey into foster care started in my early adolescent years. My parents suffered from the disease of opioid addiction — leading to a slew of homeless shelters, rehabs, and outpatient programs. At first, I lived with my brother (seven years younger than me) at my aunt’s elderly parents’ house in a completely new city.

We barely spoke to our mother, who was working hard to get better. We shared a bed in a dirty, dark attic, and the feeling of living in that home was that they were doing us a favor. We were an inconvenience. Obviously, they were kind enough to let us live there — but as an adult, I cannot help but remember the coldness and the isolation we both felt.

Soon enough, they told us we had to leave; they were in their 80s and simply couldn’t raise us. Perhaps we drained their time or resources.

I wouldn’t know because — like so many other former foster kids — the state won’t relinquish my own foster care records to me.

Once we left our relatives’ house, our social worker put us into two different homes. The memory of the day my brother was taken by car to his separate foster home is hazy. Sometimes I am violently hit with some portion of the recollection — it’s as if I could feel the breeze on my skin as I stood there watching the car leave. Other times, when I try to remember it, I come up entirely blank.

There is no way to accurately express the grief experienced by a child living a new life in a new culture, in a new city, with new people. It is almost cinematic in its abruptness; you simply wake up one day and you’re in a new world. Somehow, you’re expected to behave and be grateful — because otherwise, you could go back into the system.

And while this is hard for most, if not all, foster youth — it can be significantly worse for foster youth of color or in LGBTQIA communities.

In fact, according to The Children’s Bureau, minority children are overrepresented in foster care — especially Black foster youth, who are in foster care at 1.8 times the rate of the general population. The problem is that, according to the brief cited above, these kids face racial bias and discrimination at the hands of caseworkers and foster parents.

In Brooke Webb Lamberson’s TEDx talk, Foster the Revolution, she states, “When a community is seeking the healing of its children, they’re seeking a revolution.”

She’s not wrong.

As someone who has been speaking out and writing about my foster care experience as well as the experience of others, I often find myself wondering how to reduce the harm done to the children.

This challenge may seem big and heavy and hard to solve — and it is — but that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be on everyone’s minds all the time.

Everything else makes the news; foster youth’s stories should, too.

We need better resources for families who are dealing with poverty and addiction.

We need better assurances that homes are safe.

We need better care for youth who are placed into foster care.

More than that, people themselves are also afraid of the foster child stigma, or they’re frightened of getting too attached to a child they will only care for temporarily, as Lamberson points out.

But isn’t that the point?

Foster youth need that attachment and care. If one adult can provide stability, compassion, patience, and the ability to make space for grief, that person can change a child’s life. Although my pain was extreme, I still had my needs met by my foster families and I was encouraged to do well in school. Not every foster child is so lucky — especially when they are moved from home to home at such a young age.

Beyond helping families stay together and finding loving homes for kids, trauma reduction and resources must be at the forefront of our minds, as well.

But these resources must be taught and enforced. If we continue neglecting the huge subset of the population, we will teach our kids that are not worth fighting for. This issue requires a full-on revolution. Fortunately for me, I did eventually find a safe, lasting foster home. I lived with them for more than three years — before and through my second go-around of 10th grade and through 11th and 12th grades. I was cared for. And yet, the trauma of having to suddenly fold myself into a new life left a scar I’ve yet to heal from.

Originally published on Lisa Marie Basile on YourTango

Photo by Kinga Cichewicz on Unsplash

Family is the only thing that exists, and other things whether or not are not important.

In life it is true that nothing is foreseen.

Family is still the deciding factor, everyone needs to join hands and have a say on this issue

Family is the only thing that exists and everything else is not important

Children need to be loved more. and we should protect our families

Protecting family and children is the duty of everyone in that family.